Property from a Distinguished Collection

9✱

Zao Wou-Ki

24.10.63

signed ‘Wou-Ki [in Chinese] ZAO.’ lower right; further signed, titled and dated ‘ZAO WOU-KI “24.10.63”’ on the reverse

oil on canvas

194 x 97 cm. (76 3/8 x 38 1/4 in.)

Painted in 1963, this work is to be accompanied by a certificate of authenticity issued by the Fondation Zao Wou-Ki. This work will be referenced in the archive of the Fondation Zao Wou-Ki and will be included in the artist's forthcoming catalogue raisonné prepared by Françoise Marquet and Yann Hendgen. (Information provided by Fondation Zao Wou-Ki).

Full-Cataloguing

An artist with ‘no limits’

Zao Wou-Ki, one of the most celebrated Chinese modern artists in the world, was born in Beijing and trained at the National School of Arts in Hangzhou under the tutelage of the pioneering modern Chinese painter Lin Fengmian. Zao's move to Paris as a young artist led to the development of a singular style which moved freely between Chinese calligraphy techniques and Western-inspired abstract compositions, and the creation of works which demonstrated a profound affinity with both traditions. Enriched by his artistic encounters both in the East and West, Zao became the embodiment of his name, ‘Wou-Ki’ – the artist with 'no limits'.

The Hurricane Period, the name given to Zao’s period of practice between 1959 and 1972, is considered by many to be the apex of his extraordinary career. Referencing the wild, flowing style of cursive calligraphy that characterised Zao’s works of this period, the Hurricane Period marked the culmination of Zao’s formative training in traditional Chinese techniques and transition towards a more grand and majestic style synthesising Chinese and Western styles as well as ancient and modern elements. In a symbolic break with the past, and determined to eschew figuration going forward, Zao decided in 1958 that he would no longer give a title to his works, only marking them with their date of creation. 22.6.63 and 24.10.63, both executed within a few months of each other at the peak of the Hurricane Period, are prime examples of this new transcendental abstraction, the result of Zao’s decisive break with his esoteric ‘oracle bone’ style in favour of a more primal rendering of a search for the origins of the universe - one beyond the constraints of form. Only around 100 large scaled canvases (above a French standard size 80) from Zao’s Hurricane Period have ever come to auction.

‘Return to my deepest origins’

Paul Klee

Zeichen in Gelb (Characters in Yellow), 1937

© 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Part of a generation of Chinese artists who went abroad in the 1940s in search of artistic inspiration, Paris proved to be the catalyst for Zao’s meteoric rise to international recognition. Settling quickly into Parisian life, Zao quickly made a name for himself as an abstract gestural painter, befriending other Paris-based artists such as Pierre Soulages and Joan Miró. Originally inspired by the Impressionists, he was soon particularly taken by the work of Paul Klee, the Swiss avant-garde painter who explored the expressive potential of colour and its relationship to music, spirituality and folk art (see for example Zeichen in Gelb [Characters in Yellow], 1937). Zao continued searching for new avenues for personal expression in his work, in particular embracing lyrical abstraction - a harmonious, painterly form of abstract expressionism favoured by Hans Hartung and Georges Mathieu, amongst others.

By the mid-1950s Zao began to re-incorporate Chinese infuences more boldly into his work, at times substituting calligraphy for his previously loose and winding brushstrokes. Zao explained in 1961 ‘Although the infuence of Paris is undeniable in all my training as an artist, I also wish to say that I have gradually rediscovered China.’ He added, ‘Paradoxically, perhaps, it is to Paris that I owe this return to my deepest origins.’ (Taken from Maurice Colinon, “Ils ont choisi la France” [“They have chosen France”], Panorama Chrétien, France, no. 50, April 1961, p. 45, quoted in exh. cat., Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, ZAO WOU-KI, l’espace est silence, 1 June 2018 – 6 January 2019, p. 134.) Zao’s debt to Chinese calligraphy was manifold, a fact he freely acknowledged: ‘Calligraphy is the original source and the only guide for my painting’ (Zao Wou-Ki, adapted from unidentifed newspaper clipping, Scrapbook II, 1953 – 1960, Archives Zao Wou-Ki).

Zao’s formative early mastery of Chinese ink and brush became the roots of his artistic voice, from the inclusion of Shang Dynasty oracle bone characters in his landscape paintings in the 1950s, to the development of his whirlwind gestural brushstrokes in the 1960s that resemble the Tang Dynasty calligraphers Zhang Xu and Su Huai’s kuang cao (‘wild cursive script’ – see for example Four Poems by Zhang Xu).

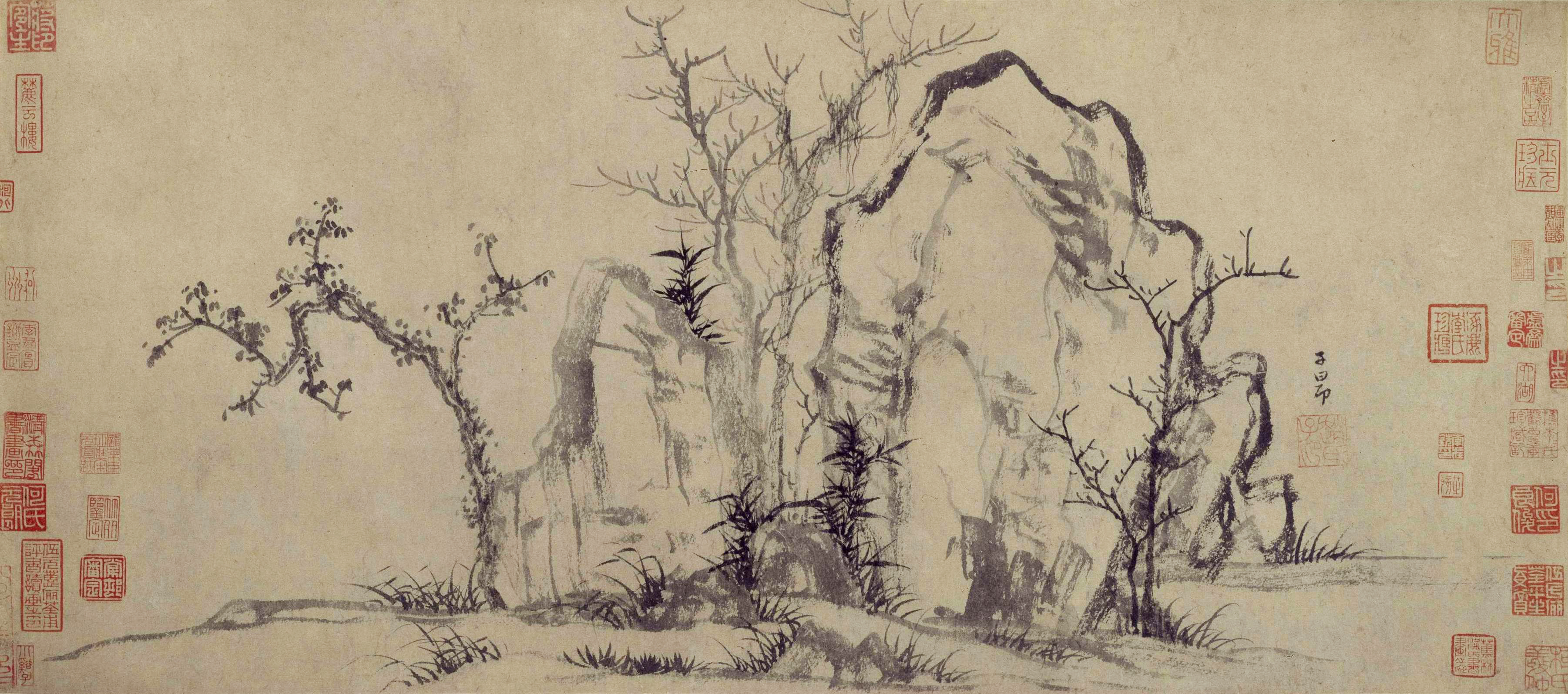

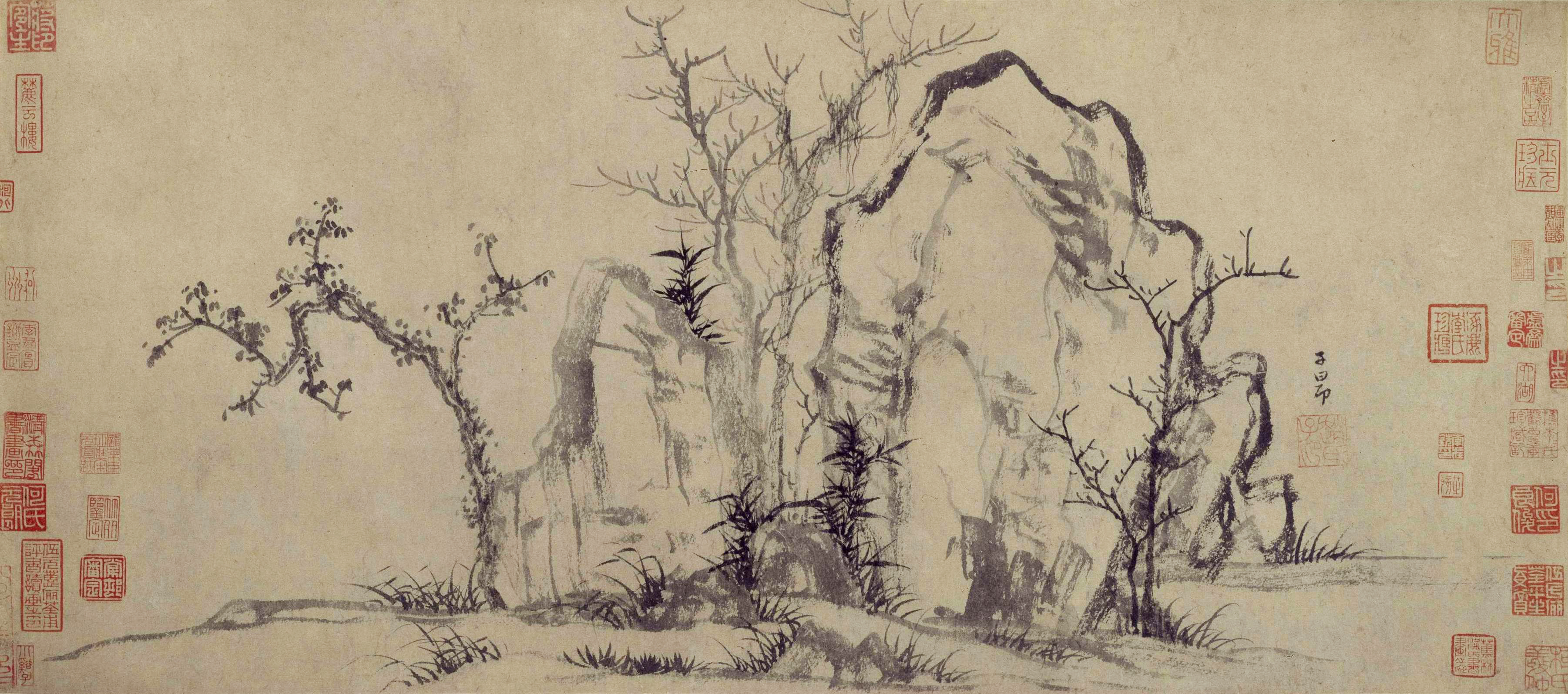

The unusual vertical format of 22.6.63 and 24.10.63 harks back to traditional Chinese hanging scrolls, whilst Zao deploys the calligraphic method of feibai (‘flying white’), where a brush (traditionally steeped in ink) smudges across silk in order to create a sense of flight (see Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees by Zhao Mengfu, which demonstrates this method). Also evident is the use of the cunfa technique (‘crack technique’) in 24.10.63 – employing a semi-dry brush to leave subtly textured traces of ink across the surface of the paper or silk – which evokes the shadows and textures of nature itself.

Zhao Mengfu

Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees, Yuan Dynasty

Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Zao also possessed an innate understanding of the possibilities of the Chinese ink medium, and recast them with a sense of immediacy using a Western medium – oil paint. Zao adapted the notion of manipulating ink as described by Tang Dynasty art historian Zhang Yanyuan in the Record of Famous Painters from all the Dynasties to produce tones that correspond to the fve colours - ‘scorched ink’, ‘concentrated ink’, ‘dense ink’, ‘light ink’ and ‘clear ink’ - which could each be further varied in degrees of wetness and concentration. Using turpentine to thin out the heavy consistency of his oil paints, Zao was able to create layers of translucent washes reminiscent of the fowing smoothness of ink on ancient literati rice paper paintings (see for example the works of Su Shi [1037-1101], the eminent poet and calligrapher).

Eye of the Hurricane

The onset of Zao’s Hurricane Period was precipitated by his travels around the globe in the 1950s. In 1957, already receiving acclaim for his ‘oracle bone’ series, Zao decided to leave Paris following the break-up of his first marriage, and journeyed westward for two years. He landed in New York in the fall of 1957.

At the vernissage of a Soulages exhibition held at New York’s renowned Kootz Gallery, Zao made the acquaintance of Philip Guston, Franz Kline, as well as Samuel Kootz himself. He visited numerous studios of his contemporaries and also received visitors at his atelier back in Paris, including Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, as well as Fernand Léger, the last of whom commented that Zao ‘was making a painting in the fog’ – a comment that touched a raw nerve with Zao, but which he admitted in his 1988 autobiography was correct (Zao Wou-Ki, adapted from Zao Wou-Ki, Autoportrait, Paris, 1988, p. 112).

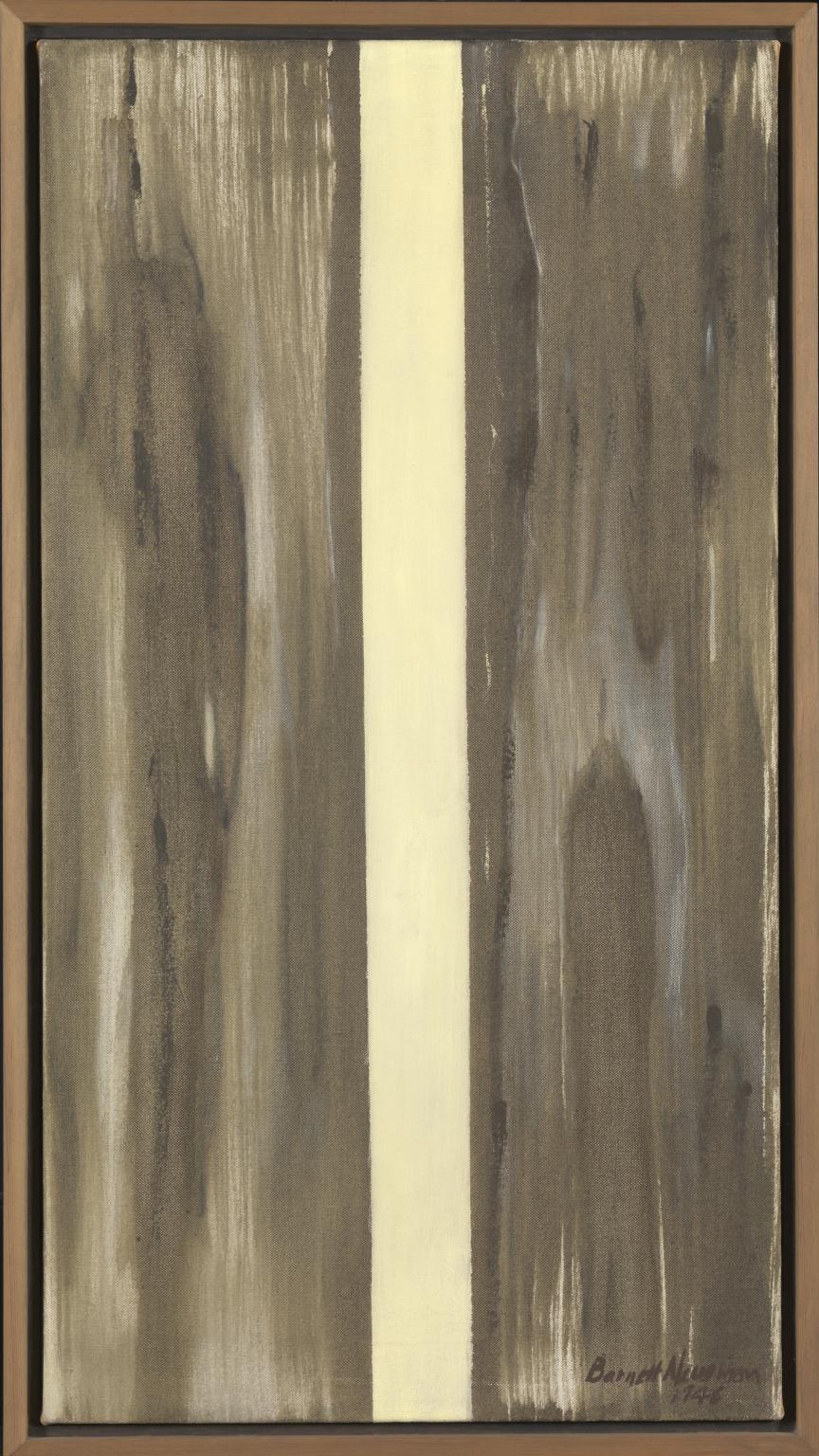

Zao found himself taken by the work of Rothko and Newman, whose work ‘burst with spontaneity, with violence and freshness’ (Autoportrait, p. 112). He particularly admired the physical element of their gestures, with paint ‘thrown’ onto canvas in ways that completely defied the traditions of the past (see for example Newman’s Moment, 1946 and Rothko’s iconic Light Red Over Black, 1957).

Re-energised, Zao recognised that he had reached the end of a cycle in his painting: ‘I wanted to paint the unseen, the breath of life, the wind, movement, the life of forms, the birth of colours and their fusion’ (Autoportrait, p. 117). Seized by a ‘hunger for creation’, he painted without stopping even at night (Autoportrait, p. 118).

Samuel Kootz, by now Zao’s dealer in the US, encouraged Zao to work on large canvases – something Zao remarked upon as unusual for a dealer because large canvases were harder to display and to sell (Autoportrait, p. 136).

Ten years at full speed

Zao’s blissful reverie came to an abrupt halt in 1960, when his beloved second wife Chan May-Kan underwent a thyroid operation. May was a Hong Kong-born actress of ‘extraordinary beauty’ whom Zao fell in love with at their first meeting during his Hong Kong stopover in 1958 (Autoportrait, p. 113). Suffering from extremely delicate health all her life, for the next decade, until her untimely death aged 41 in 1972, Zao was plunged into ‘a veritable nightmare’, describing this time as ‘ten years at full speed, the same as which I was driving a fast car’ (Autoportrait, pp. 139, 142). Painting became his refuge, and his atelier ‘the only place of peace where I held onto hope like in the middle of a storm one grips onto a small boat inundated by water from all sides’ (Autoportrait, p. 140).

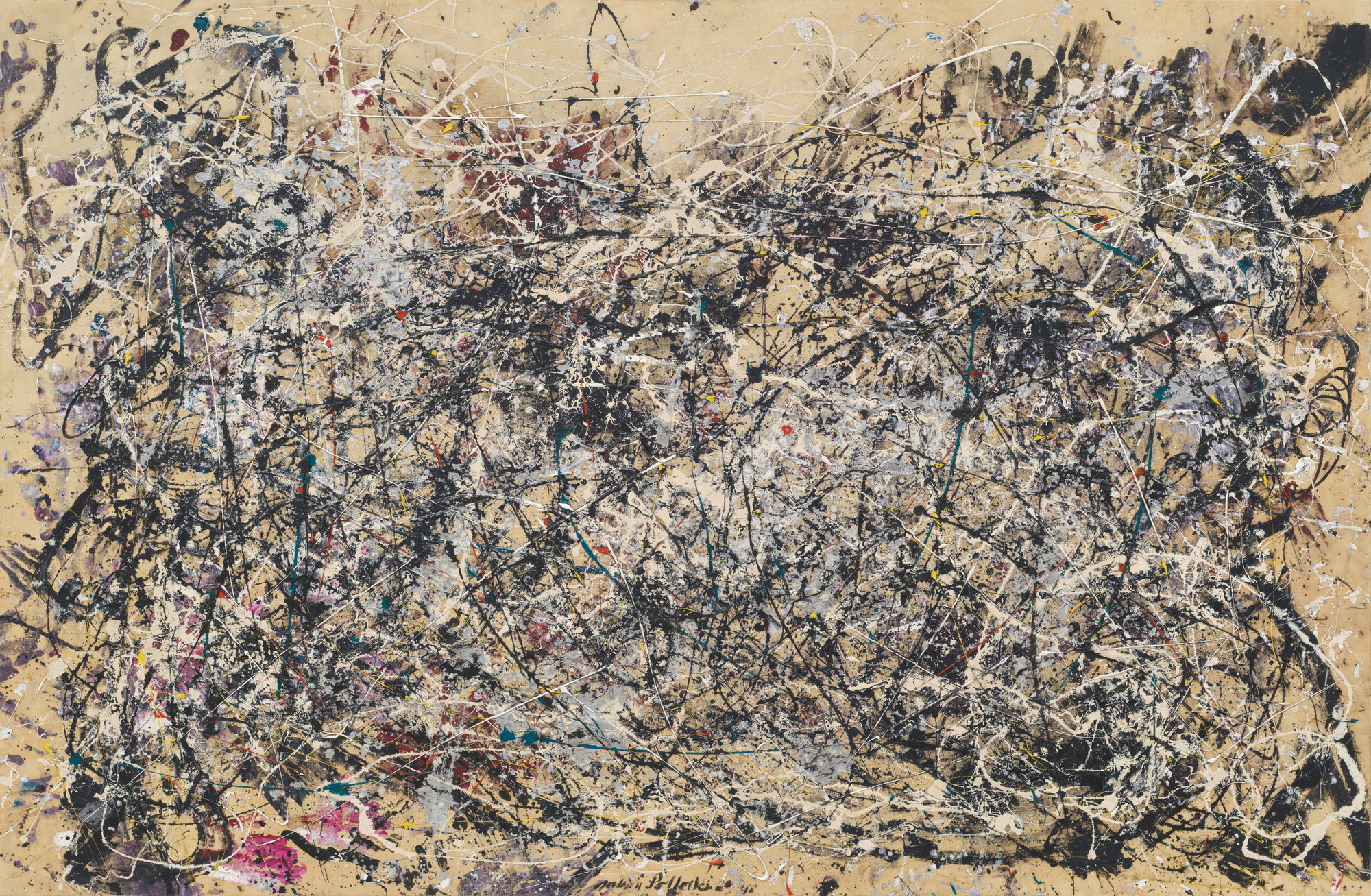

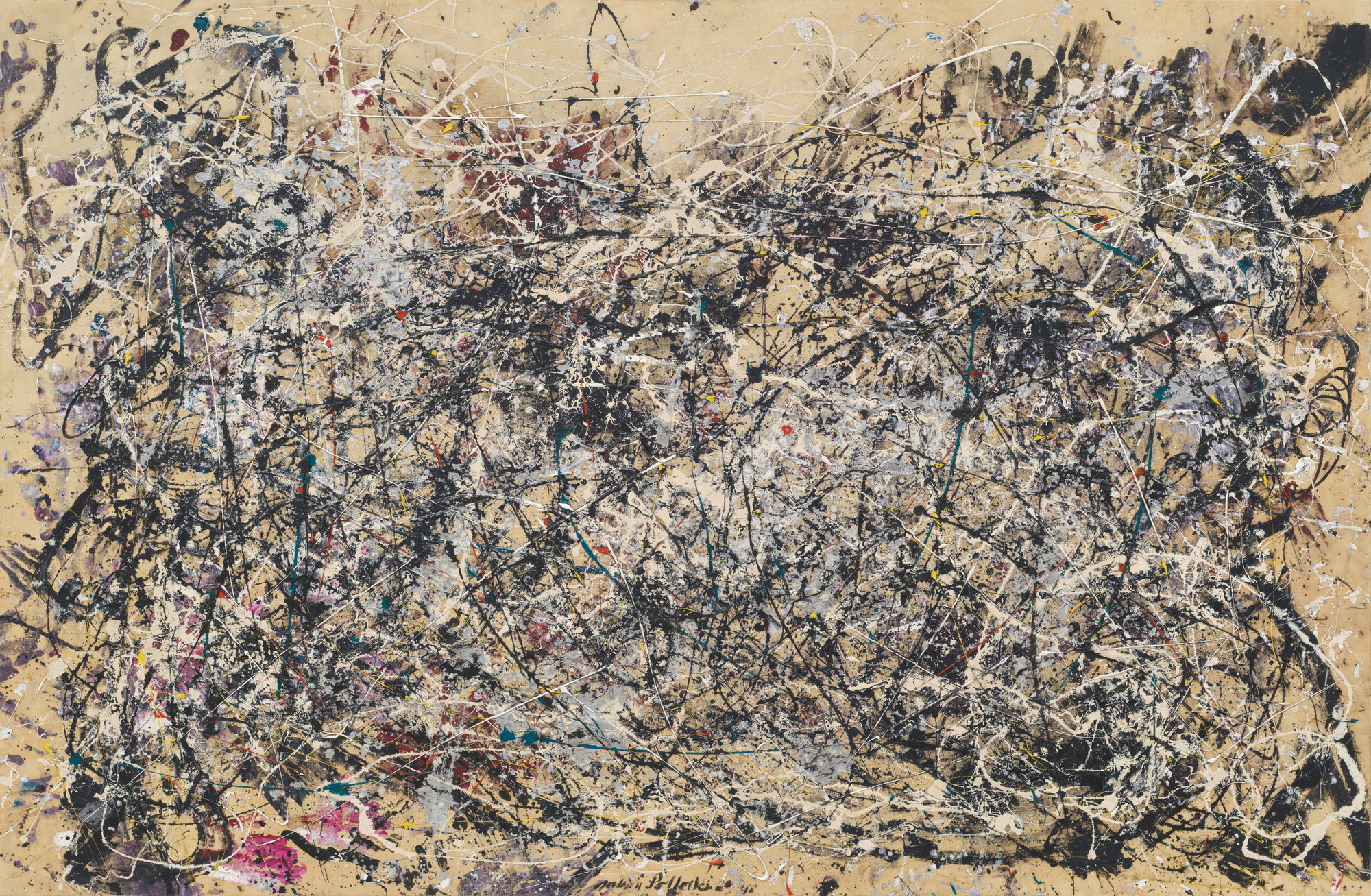

Jackson Pollock

Number 1A, 1948

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2020 The Pollock-Krasner

Foundation / Artists Rights Society

(ARS), New York

The Hurricane Period paintings of the 1960s reflect this turmoil which had upended Zao’s life, and a simultaneous yearning for peace. Zao’s singular skill in composition is proven in both 22.6.63 and 24.10.63, where the solemn stillness is ruptured by explosive lines that burst forth and fill the atmosphere, battling the elemental and chaotic. The brushwork is grand, proud and vigorous - 22.6.63’s inky-black brushstrokes leaden against a crimson red background convey a thriving, pulsating latent energy beneath the surface of the canvas, whilst in 24.10.63 sparse flying brushstrokes in stark black and brown hues are contrasted with one defiant scarlet red smudge, a nod to the centralising red dots of paint found in Jackson Pollock’s most famous action painting, Number 1A (1948). A large horizontal band of deep black and sandy-coloured exposed ground appears at the edges of each painting, creating a great impression of depth and a distant glimpse of peace beyond the tempest.

The vertical format heightens the sense of compression, whilst interwoven oil pigmented splashes and strokes, full of visual agitation, add to the sense of strong energy and motion trapped within the monumental space.

Everybody is bound by a tradition; I am bound by two

The duality of Zao’s artistic senses is manifest in the rhythm of his intercultural and fundamental influences. Traversing classical Chinese traditions and Western abstract expressionism, Zao had succeeded in producing abstract paintings that lingered in the world of landscape but hinted at the celestial realm, bridging his life experience with a meditation upon the nature of existence itself. In a 1962 article published in the magazine Preuves Zao declared: ‘Everybody is bound by a tradition; I am bound by two’.

At the heart of the Hurricane Period was the apex of an exceptional artist’s rediscovery of his Chinese roots and unique journey through the Western artistic world, as well as a twist of fate which brought one man’s exhilarating personal experience of encountering everything afresh as a stranger in a foreign land to an abrupt standstill whilst he battled the emotional turmoil of tragedy. The confluence of these circumstances gave birth to what is commonly regarded as the finest body of works of one of the few painters to have achieved recognition both in the East and West, and the dawn of a new era of Chinese modernism.

The Kootz Connection

‘The artist dies if he has nothing to say. If he has a continuity in his statement, call it by one label or another label, no movement is better than the individuals within it.’

Samuel Kootz in conversation with Dorothy Seckler for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution in New York, 13 April 1964

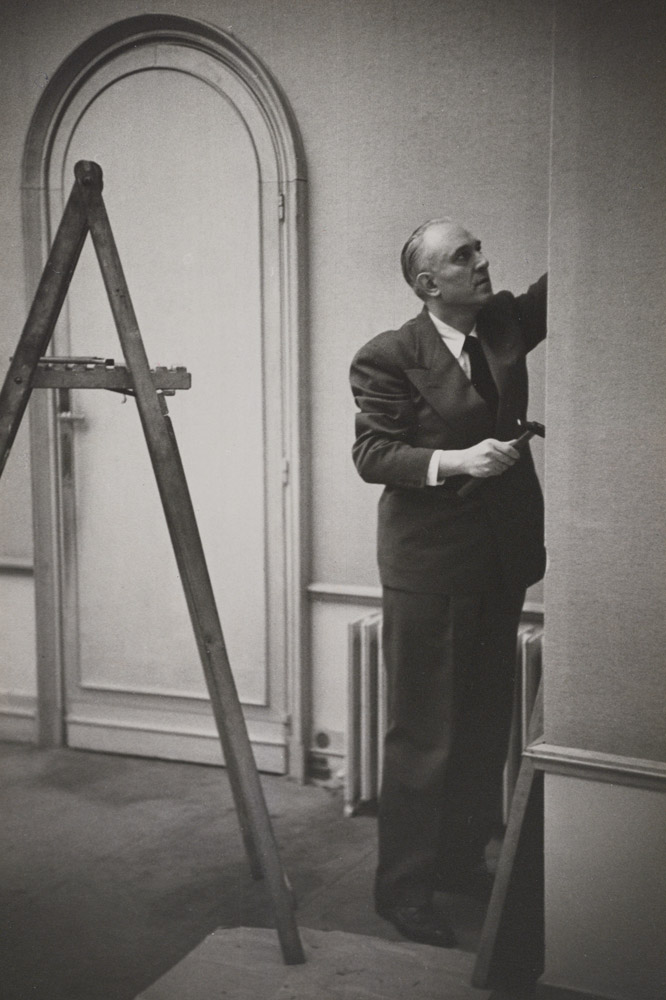

22.6.63 and 24.10.63 both passed through the hands of the famous art dealer Samuel Kootz (1898-1982). Kootz was unique in the art market: an aesthete who urged American artists to create a new form of expressive abstract art, whilst his gallery became a testing ground for championing ‘exactly what I felt was the future of American painting’ (Samuel Kootz, quoted in Archives of American Art, 'Interview of Samuel M. Kootz conducted by John Morse’, Smithsonian Institution, 2 March 1960).

Considered something of a maverick, Kootz became renowned for holding the first postwar exhibition of Picasso in America, a feat he achieved by flying to Paris ‘on a gamble’ in late 1946 and persuading the artist that sales of his work would help to support Kootz’s young and experimental protégés, including Adolph Gottlieb and Robert Motherwell. Kootz and Picasso became firm friends, and the artist granted him the privilege of selecting works directly from his studio, even suggesting in 1948 that Kootz close his gallery and become Picasso’s exclusive representative and dealer. But Kootz missed the art world too much, choosing to re-open his gallery the next year.

Kootz was a proto-activist in the art world, publishing his groundbreaking book New Frontiers in American Painting in 1943 which warned against American-centric ‘chauvinism’ in the arts - particularly in New York, which was considered the art centre of the world at the time - and promoting avant-garde artists whose artistic styles took inspiration from cultures outside America. Creating a truly international gallery, Kootz’s stable of artists would grow to include Zao Wou-Ki, Pierre Soulages, Piet Mondrian, Georges Braque and Fernand Léger, alongside contemporary American artists such as Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb

and William Baziotes.

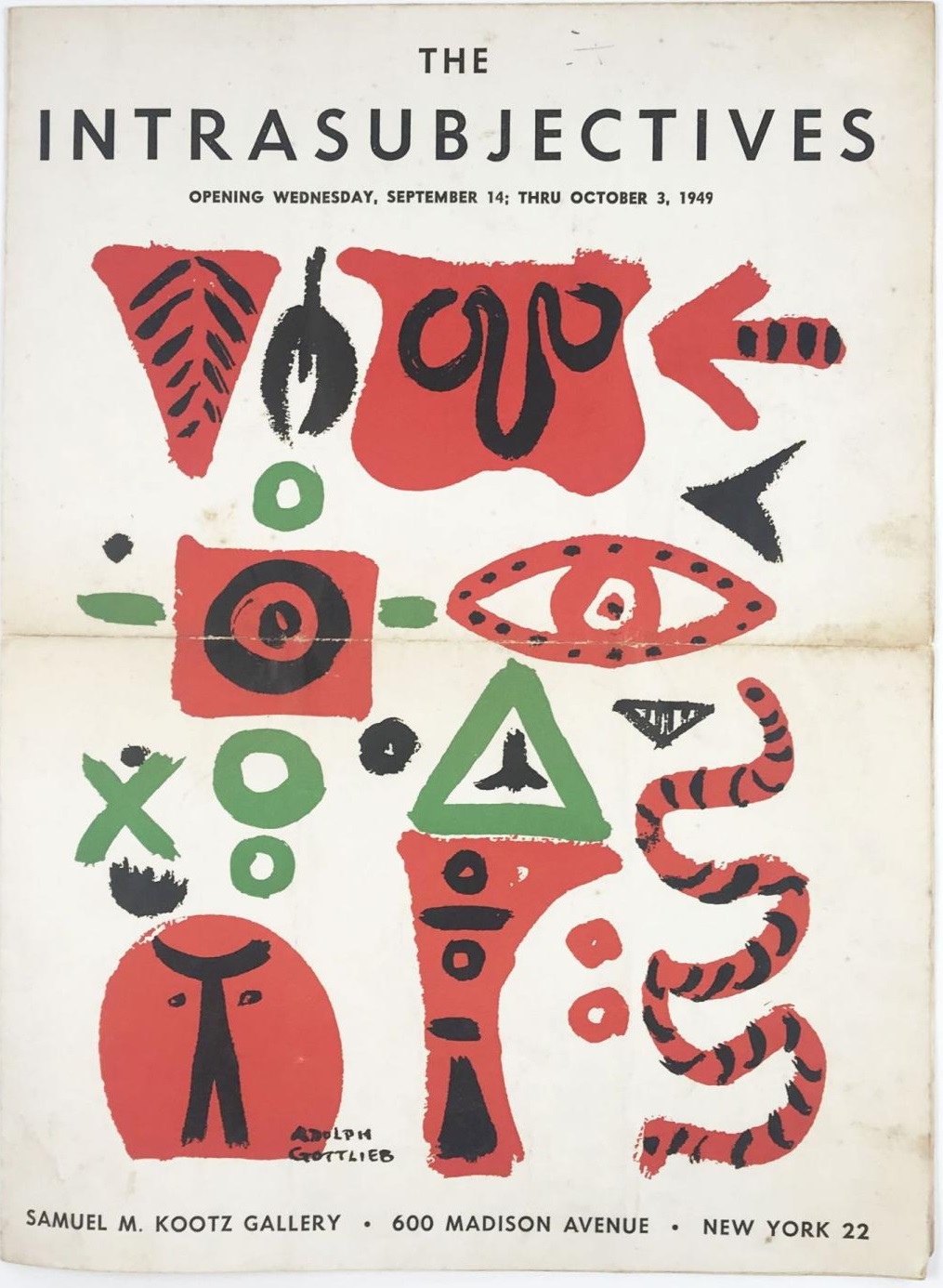

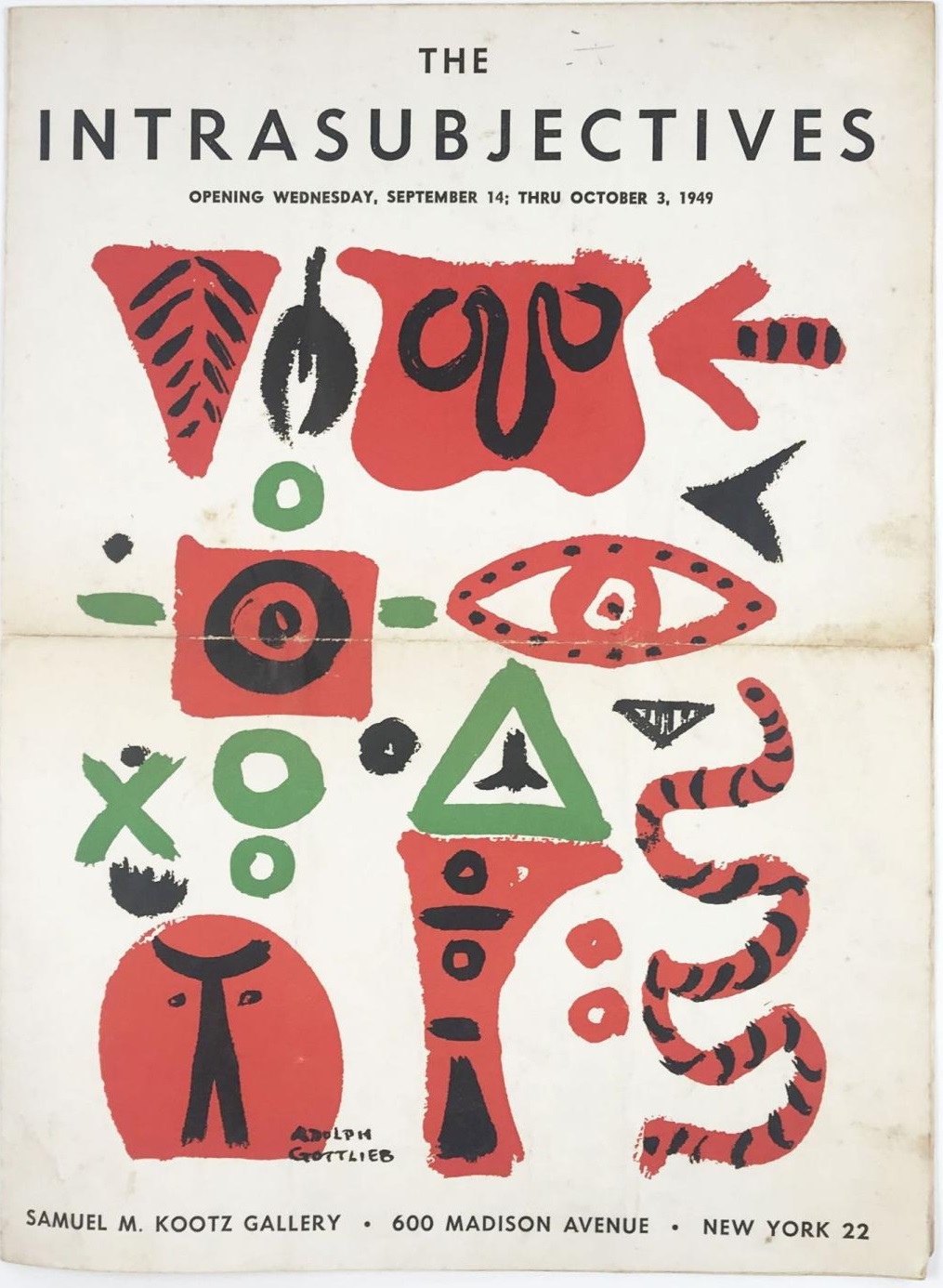

Kootz Gallery, The Intrasubjectives,14 September – 3 October 1949

The Kootz gallery’s pioneering exhibition in 1949, The Intrasubjectives, united the works of Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Hans Hofmann, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Motherwell, and others. And while the term ‘Intrasubjectives’ fell out of use, and the painters were subsequently referred to as Abstract Expressionists, the dealer’s description of their works, as outlined in the catalogue introduction, prevailed in art historical discourse.

‘The intrasubjective artist invents from personal experience, creates from an internal world rather than an external one. He makes no attempt to chronicle the American scene, exploit momentary political struggles or stimulate nostalgia through familiar objects; he deals instead with inward emotions and experiences.’

Samuel Kootz

Kootz firmly believed that ‘the modern painter is in constant search of a wall - some large expanse upon which he can employ his imagination and personal technique on a scale uninhibited by the average collector's limited space’ (Samuel Kootz, quoted in Eric Lum, ‘Pollock's Promise: Toward an Abstract Expressionist Architecture’, Assemblage, no. 39, August 1999, pp. 62-93, online), and in the 1950s he encouraged his artists to try a larger format, bringing together painters of large canvases, muralists and architects for exhibitions that redefined the relationship between the artist and audience. Zao too began to favour large scaled works (in a French standard size 80 and above) after Kootz encouraged him to shift to bigger canvases so that he could explore the development of his Hurricane Period in an unrestrained manner.

Over 20 large canvas works which passed through the Kootz Gallery have come to auction, whilst the majority remain in private or museum collections. It is exceedingly rare to have two works bearing the same distinguished provenance of the Kootz Gallery come to market at the same time.

The Collection of Walter Beardsley

Walter Beardsley was an avid art collector who amassed a world class collection of modern art, including masterpieces such as Rodin’s Fallen Caryatid and Zao Wou-Ki’s 22.6.63 and 24.10.63.

Walter Beardsley

Beardsley was a connoisseur of art whose key criterion of selection was ‘I collect what I like’. Over several decades he assembled a bold, discerning collection that showed of a keen understanding and love of art and its histories. When invited to exhibit his collection at the University of Notre Dame Art Gallery (now the Snite Museum of Art) in 1967, works by artists such as Georgia O’Keefe, Marc Chagall and Max Ernst were represented equally alongside artists of diverse cultural backgrounds and artistic movements such as Rufno Tamayo, Jean Jansem and Arthur Okamura.

Throughout his lifetime Walter Beardsley donated many of his artworks to the Snite Museum of Art, including O’Keefe’s painting Blue I (1958) and Tamayo’s Man and His Guitar (1959), which renamed one of its galleries the ‘Walter R. Beardsley Gallery of 20th- and 21st-Century Art’ in his honour.

Zao Wou-Ki, one of the most celebrated Chinese modern artists in the world, was born in Beijing and trained at the National School of Arts in Hangzhou under the tutelage of the pioneering modern Chinese painter Lin Fengmian. Zao's move to Paris as a young artist led to the development of a singular style which moved freely between Chinese calligraphy techniques and Western-inspired abstract compositions, and the creation of works which demonstrated a profound affinity with both traditions. Enriched by his artistic encounters both in the East and West, Zao became the embodiment of his name, ‘Wou-Ki’ – the artist with 'no limits'.

The Hurricane Period, the name given to Zao’s period of practice between 1959 and 1972, is considered by many to be the apex of his extraordinary career. Referencing the wild, flowing style of cursive calligraphy that characterised Zao’s works of this period, the Hurricane Period marked the culmination of Zao’s formative training in traditional Chinese techniques and transition towards a more grand and majestic style synthesising Chinese and Western styles as well as ancient and modern elements. In a symbolic break with the past, and determined to eschew figuration going forward, Zao decided in 1958 that he would no longer give a title to his works, only marking them with their date of creation. 22.6.63 and 24.10.63, both executed within a few months of each other at the peak of the Hurricane Period, are prime examples of this new transcendental abstraction, the result of Zao’s decisive break with his esoteric ‘oracle bone’ style in favour of a more primal rendering of a search for the origins of the universe - one beyond the constraints of form. Only around 100 large scaled canvases (above a French standard size 80) from Zao’s Hurricane Period have ever come to auction.

‘Return to my deepest origins’

Paul Klee

Zeichen in Gelb (Characters in Yellow), 1937

© 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Part of a generation of Chinese artists who went abroad in the 1940s in search of artistic inspiration, Paris proved to be the catalyst for Zao’s meteoric rise to international recognition. Settling quickly into Parisian life, Zao quickly made a name for himself as an abstract gestural painter, befriending other Paris-based artists such as Pierre Soulages and Joan Miró. Originally inspired by the Impressionists, he was soon particularly taken by the work of Paul Klee, the Swiss avant-garde painter who explored the expressive potential of colour and its relationship to music, spirituality and folk art (see for example Zeichen in Gelb [Characters in Yellow], 1937). Zao continued searching for new avenues for personal expression in his work, in particular embracing lyrical abstraction - a harmonious, painterly form of abstract expressionism favoured by Hans Hartung and Georges Mathieu, amongst others.

By the mid-1950s Zao began to re-incorporate Chinese infuences more boldly into his work, at times substituting calligraphy for his previously loose and winding brushstrokes. Zao explained in 1961 ‘Although the infuence of Paris is undeniable in all my training as an artist, I also wish to say that I have gradually rediscovered China.’ He added, ‘Paradoxically, perhaps, it is to Paris that I owe this return to my deepest origins.’ (Taken from Maurice Colinon, “Ils ont choisi la France” [“They have chosen France”], Panorama Chrétien, France, no. 50, April 1961, p. 45, quoted in exh. cat., Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, ZAO WOU-KI, l’espace est silence, 1 June 2018 – 6 January 2019, p. 134.) Zao’s debt to Chinese calligraphy was manifold, a fact he freely acknowledged: ‘Calligraphy is the original source and the only guide for my painting’ (Zao Wou-Ki, adapted from unidentifed newspaper clipping, Scrapbook II, 1953 – 1960, Archives Zao Wou-Ki).

Zao’s formative early mastery of Chinese ink and brush became the roots of his artistic voice, from the inclusion of Shang Dynasty oracle bone characters in his landscape paintings in the 1950s, to the development of his whirlwind gestural brushstrokes in the 1960s that resemble the Tang Dynasty calligraphers Zhang Xu and Su Huai’s kuang cao (‘wild cursive script’ – see for example Four Poems by Zhang Xu).

The unusual vertical format of 22.6.63 and 24.10.63 harks back to traditional Chinese hanging scrolls, whilst Zao deploys the calligraphic method of feibai (‘flying white’), where a brush (traditionally steeped in ink) smudges across silk in order to create a sense of flight (see Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees by Zhao Mengfu, which demonstrates this method). Also evident is the use of the cunfa technique (‘crack technique’) in 24.10.63 – employing a semi-dry brush to leave subtly textured traces of ink across the surface of the paper or silk – which evokes the shadows and textures of nature itself.

Zhao Mengfu

Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees, Yuan Dynasty

Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Zao also possessed an innate understanding of the possibilities of the Chinese ink medium, and recast them with a sense of immediacy using a Western medium – oil paint. Zao adapted the notion of manipulating ink as described by Tang Dynasty art historian Zhang Yanyuan in the Record of Famous Painters from all the Dynasties to produce tones that correspond to the fve colours - ‘scorched ink’, ‘concentrated ink’, ‘dense ink’, ‘light ink’ and ‘clear ink’ - which could each be further varied in degrees of wetness and concentration. Using turpentine to thin out the heavy consistency of his oil paints, Zao was able to create layers of translucent washes reminiscent of the fowing smoothness of ink on ancient literati rice paper paintings (see for example the works of Su Shi [1037-1101], the eminent poet and calligrapher).

Eye of the Hurricane

The onset of Zao’s Hurricane Period was precipitated by his travels around the globe in the 1950s. In 1957, already receiving acclaim for his ‘oracle bone’ series, Zao decided to leave Paris following the break-up of his first marriage, and journeyed westward for two years. He landed in New York in the fall of 1957.

At the vernissage of a Soulages exhibition held at New York’s renowned Kootz Gallery, Zao made the acquaintance of Philip Guston, Franz Kline, as well as Samuel Kootz himself. He visited numerous studios of his contemporaries and also received visitors at his atelier back in Paris, including Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, as well as Fernand Léger, the last of whom commented that Zao ‘was making a painting in the fog’ – a comment that touched a raw nerve with Zao, but which he admitted in his 1988 autobiography was correct (Zao Wou-Ki, adapted from Zao Wou-Ki, Autoportrait, Paris, 1988, p. 112).

Zao found himself taken by the work of Rothko and Newman, whose work ‘burst with spontaneity, with violence and freshness’ (Autoportrait, p. 112). He particularly admired the physical element of their gestures, with paint ‘thrown’ onto canvas in ways that completely defied the traditions of the past (see for example Newman’s Moment, 1946 and Rothko’s iconic Light Red Over Black, 1957).

Re-energised, Zao recognised that he had reached the end of a cycle in his painting: ‘I wanted to paint the unseen, the breath of life, the wind, movement, the life of forms, the birth of colours and their fusion’ (Autoportrait, p. 117). Seized by a ‘hunger for creation’, he painted without stopping even at night (Autoportrait, p. 118).

Samuel Kootz, by now Zao’s dealer in the US, encouraged Zao to work on large canvases – something Zao remarked upon as unusual for a dealer because large canvases were harder to display and to sell (Autoportrait, p. 136).

Ten years at full speed

Zao’s blissful reverie came to an abrupt halt in 1960, when his beloved second wife Chan May-Kan underwent a thyroid operation. May was a Hong Kong-born actress of ‘extraordinary beauty’ whom Zao fell in love with at their first meeting during his Hong Kong stopover in 1958 (Autoportrait, p. 113). Suffering from extremely delicate health all her life, for the next decade, until her untimely death aged 41 in 1972, Zao was plunged into ‘a veritable nightmare’, describing this time as ‘ten years at full speed, the same as which I was driving a fast car’ (Autoportrait, pp. 139, 142). Painting became his refuge, and his atelier ‘the only place of peace where I held onto hope like in the middle of a storm one grips onto a small boat inundated by water from all sides’ (Autoportrait, p. 140).

Jackson Pollock

Number 1A, 1948

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2020 The Pollock-Krasner

Foundation / Artists Rights Society

(ARS), New York

The Hurricane Period paintings of the 1960s reflect this turmoil which had upended Zao’s life, and a simultaneous yearning for peace. Zao’s singular skill in composition is proven in both 22.6.63 and 24.10.63, where the solemn stillness is ruptured by explosive lines that burst forth and fill the atmosphere, battling the elemental and chaotic. The brushwork is grand, proud and vigorous - 22.6.63’s inky-black brushstrokes leaden against a crimson red background convey a thriving, pulsating latent energy beneath the surface of the canvas, whilst in 24.10.63 sparse flying brushstrokes in stark black and brown hues are contrasted with one defiant scarlet red smudge, a nod to the centralising red dots of paint found in Jackson Pollock’s most famous action painting, Number 1A (1948). A large horizontal band of deep black and sandy-coloured exposed ground appears at the edges of each painting, creating a great impression of depth and a distant glimpse of peace beyond the tempest.

The vertical format heightens the sense of compression, whilst interwoven oil pigmented splashes and strokes, full of visual agitation, add to the sense of strong energy and motion trapped within the monumental space.

Everybody is bound by a tradition; I am bound by two

The duality of Zao’s artistic senses is manifest in the rhythm of his intercultural and fundamental influences. Traversing classical Chinese traditions and Western abstract expressionism, Zao had succeeded in producing abstract paintings that lingered in the world of landscape but hinted at the celestial realm, bridging his life experience with a meditation upon the nature of existence itself. In a 1962 article published in the magazine Preuves Zao declared: ‘Everybody is bound by a tradition; I am bound by two’.

At the heart of the Hurricane Period was the apex of an exceptional artist’s rediscovery of his Chinese roots and unique journey through the Western artistic world, as well as a twist of fate which brought one man’s exhilarating personal experience of encountering everything afresh as a stranger in a foreign land to an abrupt standstill whilst he battled the emotional turmoil of tragedy. The confluence of these circumstances gave birth to what is commonly regarded as the finest body of works of one of the few painters to have achieved recognition both in the East and West, and the dawn of a new era of Chinese modernism.

The Kootz Connection

‘The artist dies if he has nothing to say. If he has a continuity in his statement, call it by one label or another label, no movement is better than the individuals within it.’

Samuel Kootz in conversation with Dorothy Seckler for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution in New York, 13 April 1964

22.6.63 and 24.10.63 both passed through the hands of the famous art dealer Samuel Kootz (1898-1982). Kootz was unique in the art market: an aesthete who urged American artists to create a new form of expressive abstract art, whilst his gallery became a testing ground for championing ‘exactly what I felt was the future of American painting’ (Samuel Kootz, quoted in Archives of American Art, 'Interview of Samuel M. Kootz conducted by John Morse’, Smithsonian Institution, 2 March 1960).

Considered something of a maverick, Kootz became renowned for holding the first postwar exhibition of Picasso in America, a feat he achieved by flying to Paris ‘on a gamble’ in late 1946 and persuading the artist that sales of his work would help to support Kootz’s young and experimental protégés, including Adolph Gottlieb and Robert Motherwell. Kootz and Picasso became firm friends, and the artist granted him the privilege of selecting works directly from his studio, even suggesting in 1948 that Kootz close his gallery and become Picasso’s exclusive representative and dealer. But Kootz missed the art world too much, choosing to re-open his gallery the next year.

Kootz was a proto-activist in the art world, publishing his groundbreaking book New Frontiers in American Painting in 1943 which warned against American-centric ‘chauvinism’ in the arts - particularly in New York, which was considered the art centre of the world at the time - and promoting avant-garde artists whose artistic styles took inspiration from cultures outside America. Creating a truly international gallery, Kootz’s stable of artists would grow to include Zao Wou-Ki, Pierre Soulages, Piet Mondrian, Georges Braque and Fernand Léger, alongside contemporary American artists such as Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb

and William Baziotes.

Kootz Gallery, The Intrasubjectives,14 September – 3 October 1949

The Kootz gallery’s pioneering exhibition in 1949, The Intrasubjectives, united the works of Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Hans Hofmann, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Motherwell, and others. And while the term ‘Intrasubjectives’ fell out of use, and the painters were subsequently referred to as Abstract Expressionists, the dealer’s description of their works, as outlined in the catalogue introduction, prevailed in art historical discourse.

‘The intrasubjective artist invents from personal experience, creates from an internal world rather than an external one. He makes no attempt to chronicle the American scene, exploit momentary political struggles or stimulate nostalgia through familiar objects; he deals instead with inward emotions and experiences.’

Samuel Kootz

Kootz firmly believed that ‘the modern painter is in constant search of a wall - some large expanse upon which he can employ his imagination and personal technique on a scale uninhibited by the average collector's limited space’ (Samuel Kootz, quoted in Eric Lum, ‘Pollock's Promise: Toward an Abstract Expressionist Architecture’, Assemblage, no. 39, August 1999, pp. 62-93, online), and in the 1950s he encouraged his artists to try a larger format, bringing together painters of large canvases, muralists and architects for exhibitions that redefined the relationship between the artist and audience. Zao too began to favour large scaled works (in a French standard size 80 and above) after Kootz encouraged him to shift to bigger canvases so that he could explore the development of his Hurricane Period in an unrestrained manner.

Over 20 large canvas works which passed through the Kootz Gallery have come to auction, whilst the majority remain in private or museum collections. It is exceedingly rare to have two works bearing the same distinguished provenance of the Kootz Gallery come to market at the same time.

The Collection of Walter Beardsley

Walter Beardsley was an avid art collector who amassed a world class collection of modern art, including masterpieces such as Rodin’s Fallen Caryatid and Zao Wou-Ki’s 22.6.63 and 24.10.63.

Walter Beardsley

Beardsley was a connoisseur of art whose key criterion of selection was ‘I collect what I like’. Over several decades he assembled a bold, discerning collection that showed of a keen understanding and love of art and its histories. When invited to exhibit his collection at the University of Notre Dame Art Gallery (now the Snite Museum of Art) in 1967, works by artists such as Georgia O’Keefe, Marc Chagall and Max Ernst were represented equally alongside artists of diverse cultural backgrounds and artistic movements such as Rufno Tamayo, Jean Jansem and Arthur Okamura.

Throughout his lifetime Walter Beardsley donated many of his artworks to the Snite Museum of Art, including O’Keefe’s painting Blue I (1958) and Tamayo’s Man and His Guitar (1959), which renamed one of its galleries the ‘Walter R. Beardsley Gallery of 20th- and 21st-Century Art’ in his honour.