Property from an Important Collection

7Ο◆✱Ж

Liu Ye

Choir of Angels (Red)

signed and dated 'Ye [in Chinese] liu ye 99' lower right

oil on canvas

169.1 x 199.2 cm. (66 5/8 x 78 3/8 in.)

Painted in 1999.

Full-Cataloguing

Chinese contemporary painter Liu Ye is known for his dream-like imagery inspired by his childhood love of fairytales and formative education in Europe, giving rise to a singular body of work rich in aesthetic, historical and literary meaning. Distinguished from his fellow Chinese painters by a prevailing love of wonder and mystery, Liu Ye’s bold and meditative paintings challenge viewers to participate in a world liberated from the concrete and the present.

Childhood memory, fairy tales and European influence

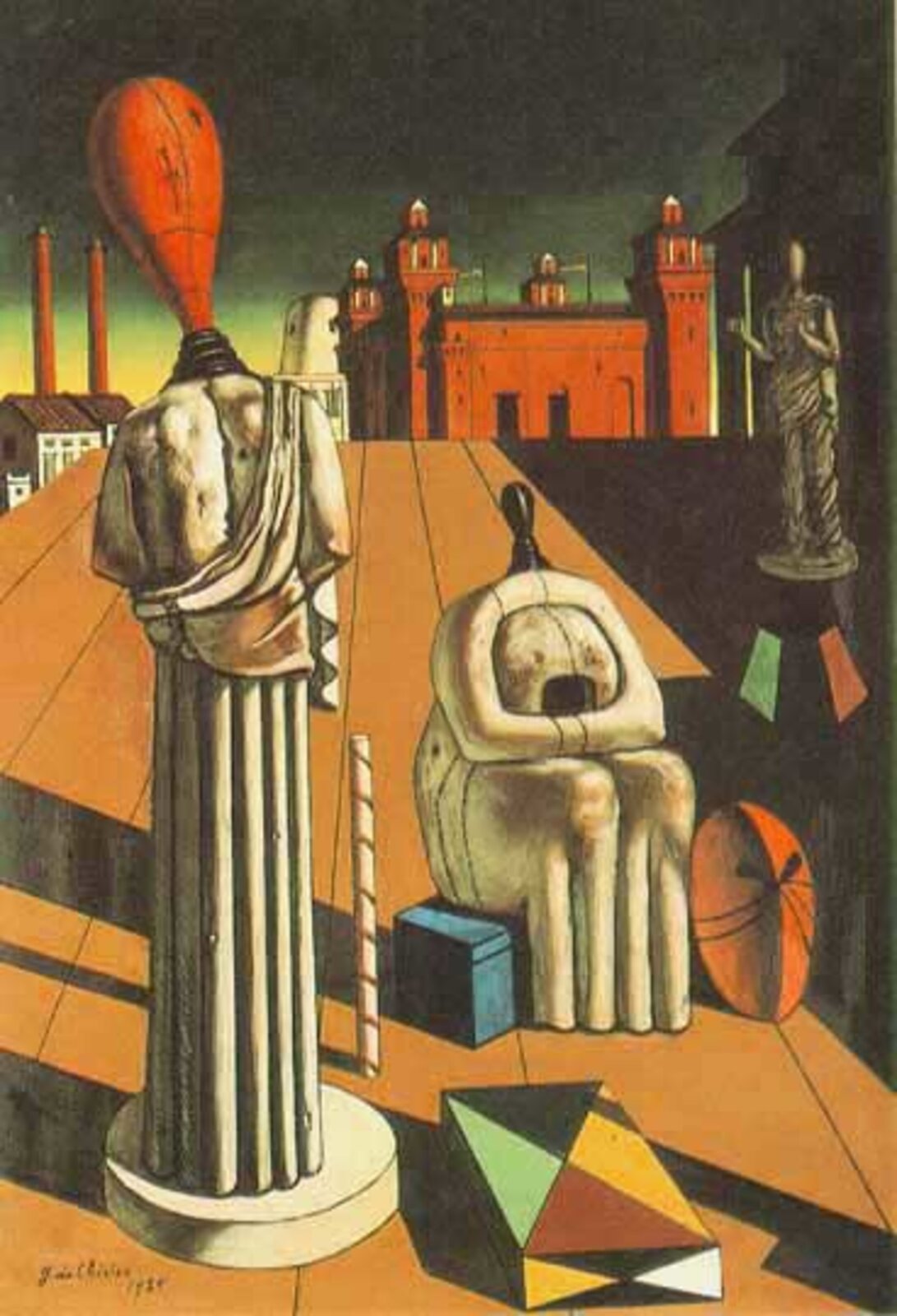

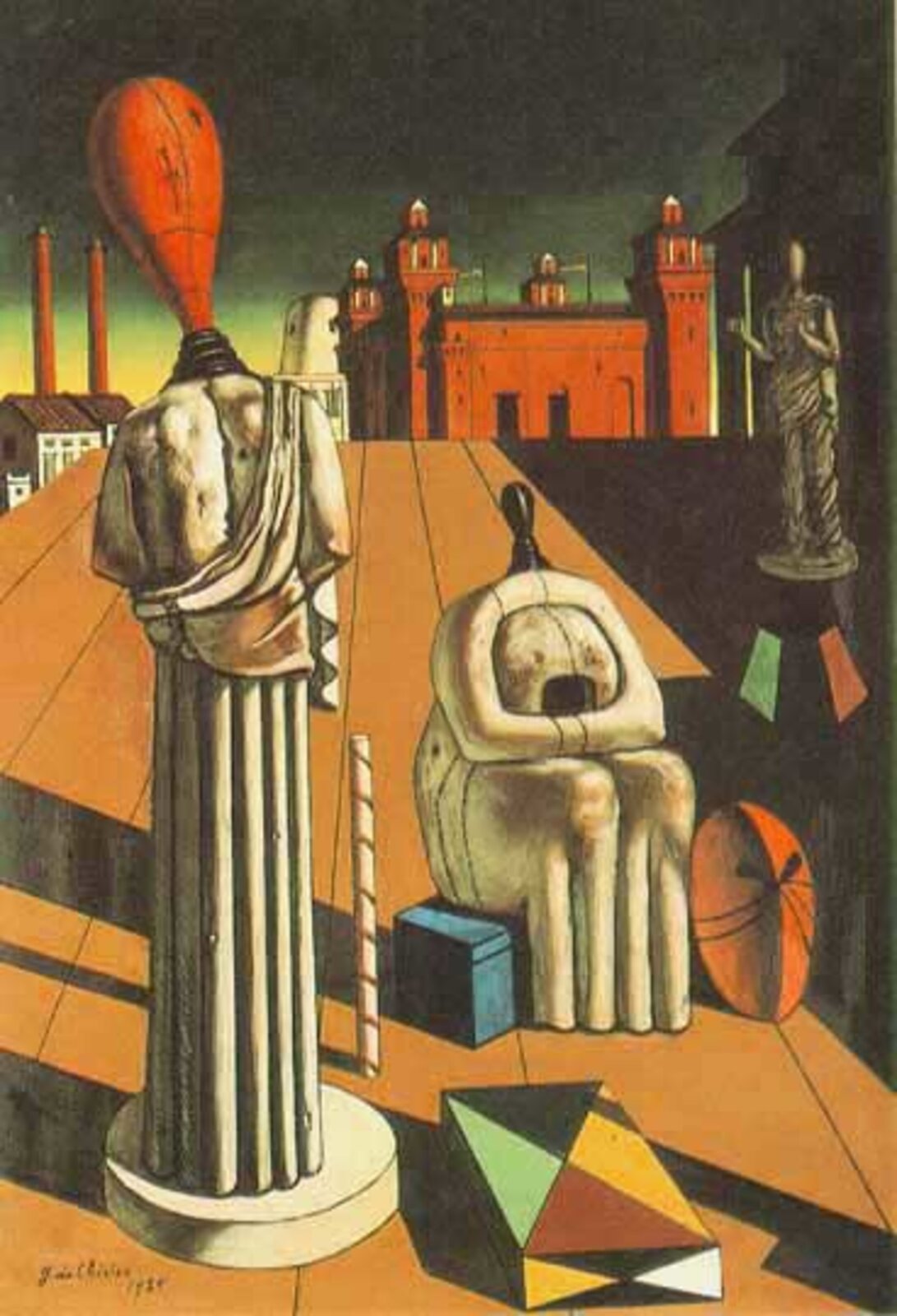

Giorgio de Chirico

The Disquieting Muses, 1916

Born in Beijing two years before the Cultural Revolution began, Liu grew up in a society rigidly controlled by the state. Liu Ye's father was a famous children’s playwright, and although many Western books were banned at the time, his parents had secreted a trove of Western story books in a large black chest under his bed, including the works of Hans Christian Andersen and Tolstoy. Liu Ye became an imaginative child, and this quality combined with the manner of his upbringing in China would later prove a key source of his inspiration and way of seeing: ‘In my earlier days, [inspiration] came from my imagination, childhood memories, and the societal background’ (Liu Ye, quoted in Cheryl Zhao, ‘Artist Liu Ye on His New Catalogue Raisonné and the Rise of Chinese Collectors’, Jing Daily, 10 December 2015, online).

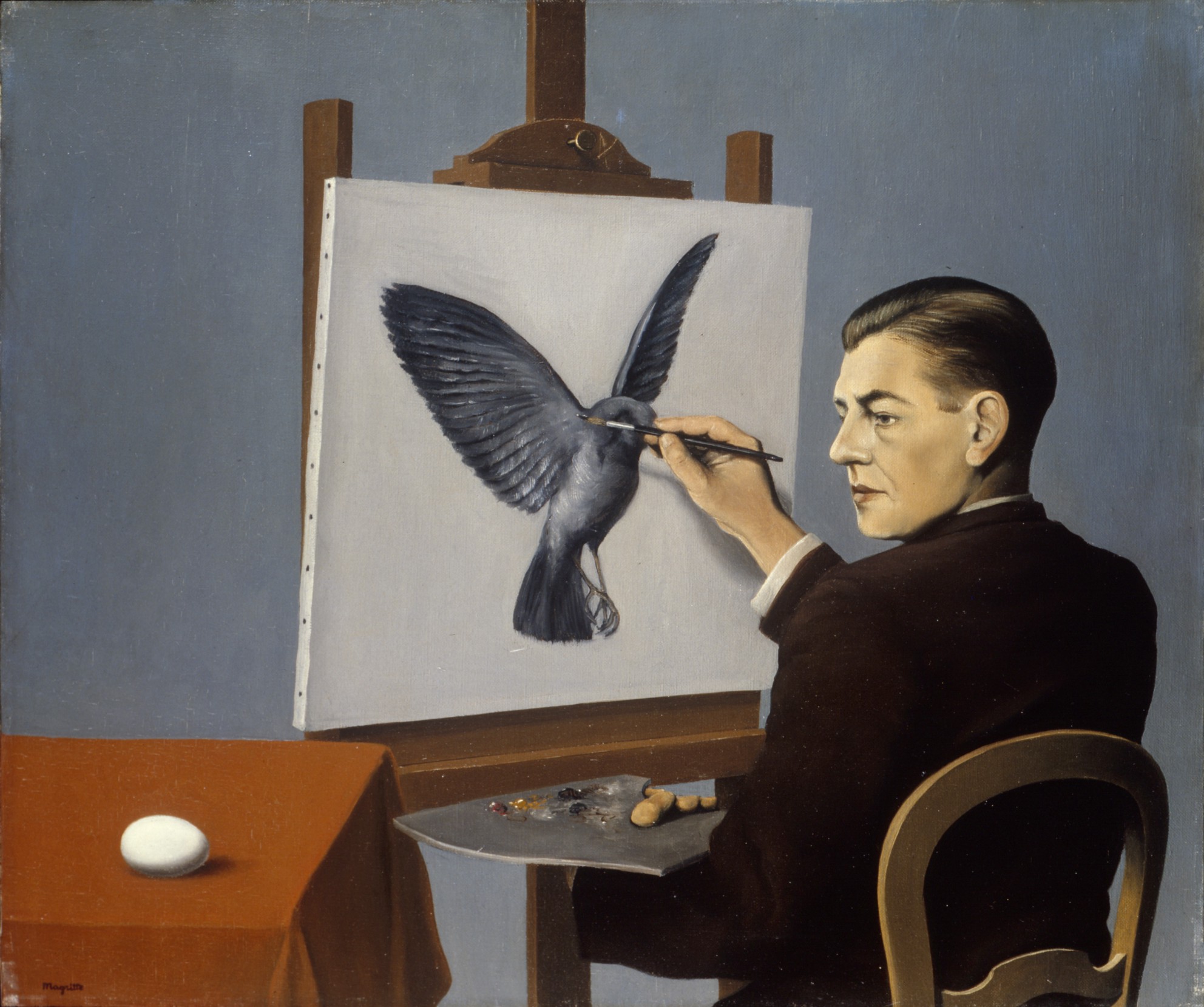

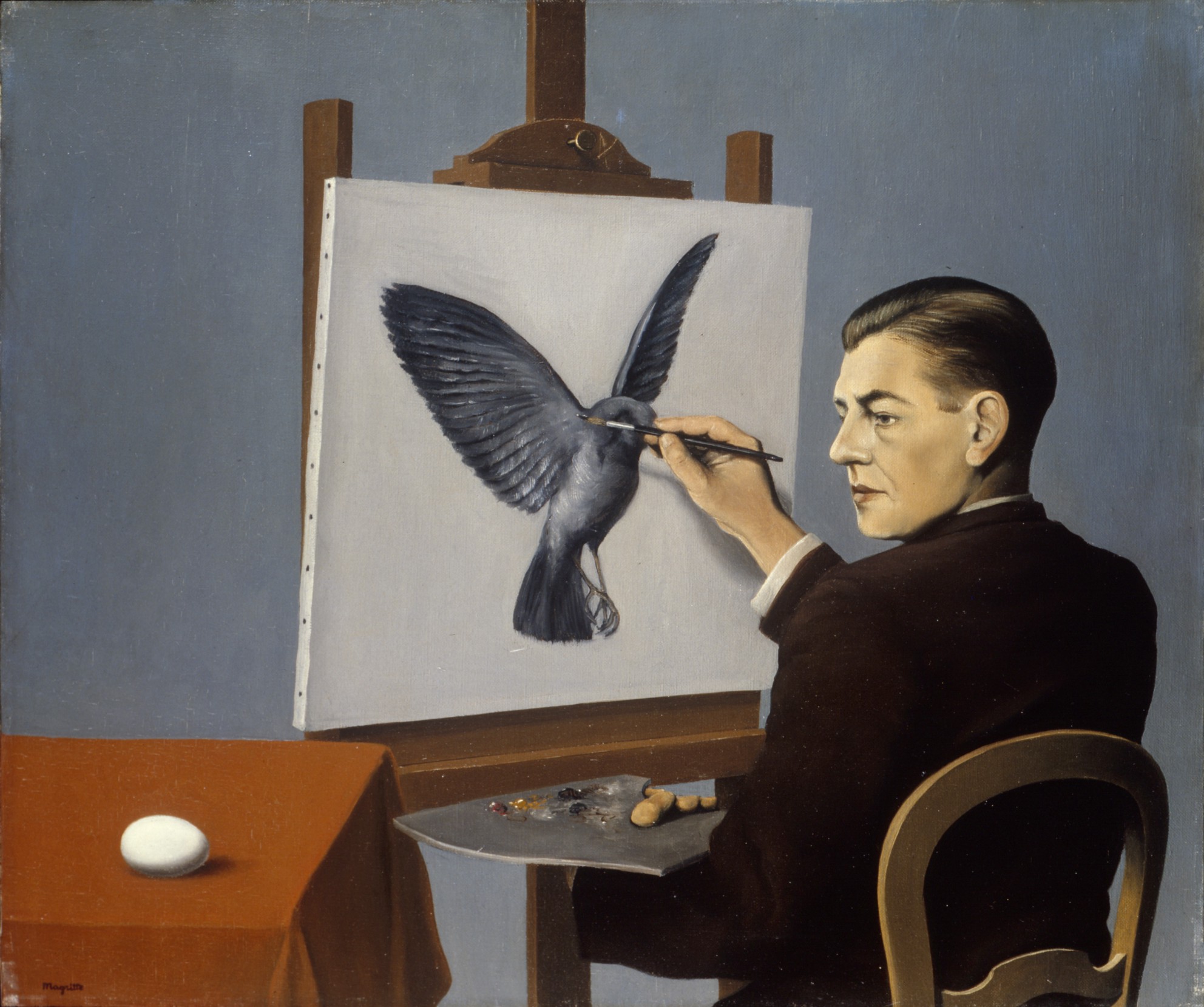

René Magritte

Clairvoyance, 1936

Liu Ye’s knowledge of Western cultural history was formulated during the years he spent in Europe. In 1990, having completed his studies in mural painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, Liu Ye continued his studies for another four years at Berlin's Universität der Künste, and then took up a six-month residency at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam in 1998. During these years Liu Ye became influenced by European artists such as Piet Mondrian (whose grid-based paintings became a recurring motif in his paintings), Dick Bruna (in particular his iconic creation Miffy), as well as René Magritte, the Belgian Surrealist. Explaining why he was drawn to these artists, Liu Ye elaborated: ‘In my earlier days, my art was more about the imaginary. At that time, I was influenced by Italian Metaphysical Art and Surrealism; René Magritte is one of my favourite artists’ (Liu Ye, quoted in Cheryl Zhao, ‘Artist Liu Ye on His New Catalogue Raisonné and the Rise of Chinese Collectors’, Jing Daily, 10 December 2015, online).

Borrowing from fairy tales and artistic encounters in Europe, the guileless characters with tiny cherub wings emerged to occupy the spotlight in Liu’s paintings. Depicting these childish figures on theatre stages or in landscapes, fully immersed in their own worlds and unaware of the concurrent catastrophic scenes of sinking ships and flying bombers (see for example in Bright Road, 1995), the artist has imbued a deliberately humorous yet ridiculous mood in his works, injecting a sense of Surrealism and irony.

The curtain sets the stage

Chorus is one of Liu Ye’s earliest paintings and part of his iconic ‘red curtain’ series, which was executed shortly after his return from Europe to China. The ‘red curtain’ paintings nod to the carefully balanced, methodical compositions of René Magritte and Georgio de Chirico, which saw objects and scenes depicted in a realistic yet unsettling manner. Their preference for Classically-inspired forms and volumes (see for example the fluted columns in de Chirico’s The Disquieting Muses, 1916) echo the modelling and theatricality of Liu Ye’s red curtain motif. The unique composition of the present lot features eleven cherubic singers, which was later rendered in shades of blue and re-created into lithography by Liu Ye in the early 2000s.

The curtain is a double-edged symbol: it acts to reveal, immediately recalling to mind Balthus’ The Room (within Liu’s oeuvre for example, please see the warship in Untitled, 1997-8) and yet its primary function is to conceal. In this scene, the emotionless singing cherubs are arranged neatly to project a sense of order and discipline so unusual among a group of boisterous children that this harmonious imagery appears to be deceiving. Speaking of the persistent human desire to question reality and appearances, Magritte explained: ‘We are surrounded by curtains. We only perceive the world behind a curtain of semblance. At the same time, an object needs to be covered in order to be recognised at all’ (no citation available). Rich in evocative mystery, the curtain becomes an enduring motif in Liu’s works to create a profound sense of spatial and temporal dislocation, the interplay of truth and illusion teases with preconditioned perceptions of reality and conventional ways of seeing.

A world ‘covered up in red’

The rich crimson red which colours the backdrop and subjects of Chorus adds another layer of meaning. A signifier of joy and luck in Chinese culture, the colour red was also transformed irrevocably into an ideological colour monopolised by revolutionary propaganda: the Chinese national flag ‘dyed red’ by the blood of revolutionaries, the Red Army of the Communist Party, the red scarf worn by the Young Pioneers, and the ‘red heart’ of party loyalists and supporters of socialism: ‘I grew up in a world that was covered up in red – the red sun, the red flag and red scarves. As for green pines and cedars, or sunflowers, they were usually just foils for the symbolism of red,’ recalled Liu Ye. Associating the colour red with the prevailing visual emblem of his childhood days, the singing cherubs in Chorus subtly references the rosy-cheeked children featured in popular propaganda, while the stage setting and the deployment of a rounded spotlight dramatically amplify the theatrical effect of the imagery.

Interestingly, the red and blue renditions of Chorus both speak to a visual experience triggered by childhood memory, as the artist recalls using coloured pencils with ‘red for the sun and the national flag, yellow for sunflowers and sunlight, and blue for the ocean and sky.’ These represent Liu’s earliest use of primary colours that extends to his paintings to emphasise a personal experience within a collective society. The transition from one dominant colour to another mirrors Pablo Picasso’s shift from his Blue Period to Rose Period – from depicting a state of poverty and rejection to finding love and companionship - it corresponds to the psychological states prompted by tragedy, love, relationship within the social conditions of the time. For Liu, red is a tool of reminiscence that reconnects the artist’s memory with his homeland, and the development to blue presaged a period of more internal exploration into a more abstract form of expression.

Yet Chorus does not dwell on the past – Liu’s time in Berlin came at a crucial moment in Chinese modern history, allowing him to develop his work independent of political developments back home. The stage, once associated with the plays of his father and subsequently the ‘red’ propaganda of revolutionary operas, is instead concealed in Chorus by a curtain which draws a symbolic close on history. The assembly of singers with faces of rotund childlike innocence points to nostalgic reflection on childhood experience. Liu Ye liberates symbols of the past using the power of imagination and fairy tales, allowing new meanings and associations from both Eastern and Western cultural traditions to interact freely in the theatrical red curtained setting. In this sense Chorus is a symbol for the artist himself – liberated to investigate the intersections of history and representation, Liu Ye has developed a distinct visual vocabulary that transcends traditional Eastern and Western art historical categories.

The artist was recently the subject of a solo exhibition at Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai (2018 - 19), and his works are held in numerous public collections, including the Long Museum (Shanghai), M+ Sigg Collection (Hong Kong), and Today Art Museum (Beijing). The artist is represented by David Zwirner.

Childhood memory, fairy tales and European influence

Giorgio de Chirico

The Disquieting Muses, 1916

Born in Beijing two years before the Cultural Revolution began, Liu grew up in a society rigidly controlled by the state. Liu Ye's father was a famous children’s playwright, and although many Western books were banned at the time, his parents had secreted a trove of Western story books in a large black chest under his bed, including the works of Hans Christian Andersen and Tolstoy. Liu Ye became an imaginative child, and this quality combined with the manner of his upbringing in China would later prove a key source of his inspiration and way of seeing: ‘In my earlier days, [inspiration] came from my imagination, childhood memories, and the societal background’ (Liu Ye, quoted in Cheryl Zhao, ‘Artist Liu Ye on His New Catalogue Raisonné and the Rise of Chinese Collectors’, Jing Daily, 10 December 2015, online).

René Magritte

Clairvoyance, 1936

Liu Ye’s knowledge of Western cultural history was formulated during the years he spent in Europe. In 1990, having completed his studies in mural painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, Liu Ye continued his studies for another four years at Berlin's Universität der Künste, and then took up a six-month residency at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam in 1998. During these years Liu Ye became influenced by European artists such as Piet Mondrian (whose grid-based paintings became a recurring motif in his paintings), Dick Bruna (in particular his iconic creation Miffy), as well as René Magritte, the Belgian Surrealist. Explaining why he was drawn to these artists, Liu Ye elaborated: ‘In my earlier days, my art was more about the imaginary. At that time, I was influenced by Italian Metaphysical Art and Surrealism; René Magritte is one of my favourite artists’ (Liu Ye, quoted in Cheryl Zhao, ‘Artist Liu Ye on His New Catalogue Raisonné and the Rise of Chinese Collectors’, Jing Daily, 10 December 2015, online).

Borrowing from fairy tales and artistic encounters in Europe, the guileless characters with tiny cherub wings emerged to occupy the spotlight in Liu’s paintings. Depicting these childish figures on theatre stages or in landscapes, fully immersed in their own worlds and unaware of the concurrent catastrophic scenes of sinking ships and flying bombers (see for example in Bright Road, 1995), the artist has imbued a deliberately humorous yet ridiculous mood in his works, injecting a sense of Surrealism and irony.

The curtain sets the stage

Chorus is one of Liu Ye’s earliest paintings and part of his iconic ‘red curtain’ series, which was executed shortly after his return from Europe to China. The ‘red curtain’ paintings nod to the carefully balanced, methodical compositions of René Magritte and Georgio de Chirico, which saw objects and scenes depicted in a realistic yet unsettling manner. Their preference for Classically-inspired forms and volumes (see for example the fluted columns in de Chirico’s The Disquieting Muses, 1916) echo the modelling and theatricality of Liu Ye’s red curtain motif. The unique composition of the present lot features eleven cherubic singers, which was later rendered in shades of blue and re-created into lithography by Liu Ye in the early 2000s.

The curtain is a double-edged symbol: it acts to reveal, immediately recalling to mind Balthus’ The Room (within Liu’s oeuvre for example, please see the warship in Untitled, 1997-8) and yet its primary function is to conceal. In this scene, the emotionless singing cherubs are arranged neatly to project a sense of order and discipline so unusual among a group of boisterous children that this harmonious imagery appears to be deceiving. Speaking of the persistent human desire to question reality and appearances, Magritte explained: ‘We are surrounded by curtains. We only perceive the world behind a curtain of semblance. At the same time, an object needs to be covered in order to be recognised at all’ (no citation available). Rich in evocative mystery, the curtain becomes an enduring motif in Liu’s works to create a profound sense of spatial and temporal dislocation, the interplay of truth and illusion teases with preconditioned perceptions of reality and conventional ways of seeing.

A world ‘covered up in red’

The rich crimson red which colours the backdrop and subjects of Chorus adds another layer of meaning. A signifier of joy and luck in Chinese culture, the colour red was also transformed irrevocably into an ideological colour monopolised by revolutionary propaganda: the Chinese national flag ‘dyed red’ by the blood of revolutionaries, the Red Army of the Communist Party, the red scarf worn by the Young Pioneers, and the ‘red heart’ of party loyalists and supporters of socialism: ‘I grew up in a world that was covered up in red – the red sun, the red flag and red scarves. As for green pines and cedars, or sunflowers, they were usually just foils for the symbolism of red,’ recalled Liu Ye. Associating the colour red with the prevailing visual emblem of his childhood days, the singing cherubs in Chorus subtly references the rosy-cheeked children featured in popular propaganda, while the stage setting and the deployment of a rounded spotlight dramatically amplify the theatrical effect of the imagery.

Interestingly, the red and blue renditions of Chorus both speak to a visual experience triggered by childhood memory, as the artist recalls using coloured pencils with ‘red for the sun and the national flag, yellow for sunflowers and sunlight, and blue for the ocean and sky.’ These represent Liu’s earliest use of primary colours that extends to his paintings to emphasise a personal experience within a collective society. The transition from one dominant colour to another mirrors Pablo Picasso’s shift from his Blue Period to Rose Period – from depicting a state of poverty and rejection to finding love and companionship - it corresponds to the psychological states prompted by tragedy, love, relationship within the social conditions of the time. For Liu, red is a tool of reminiscence that reconnects the artist’s memory with his homeland, and the development to blue presaged a period of more internal exploration into a more abstract form of expression.

Yet Chorus does not dwell on the past – Liu’s time in Berlin came at a crucial moment in Chinese modern history, allowing him to develop his work independent of political developments back home. The stage, once associated with the plays of his father and subsequently the ‘red’ propaganda of revolutionary operas, is instead concealed in Chorus by a curtain which draws a symbolic close on history. The assembly of singers with faces of rotund childlike innocence points to nostalgic reflection on childhood experience. Liu Ye liberates symbols of the past using the power of imagination and fairy tales, allowing new meanings and associations from both Eastern and Western cultural traditions to interact freely in the theatrical red curtained setting. In this sense Chorus is a symbol for the artist himself – liberated to investigate the intersections of history and representation, Liu Ye has developed a distinct visual vocabulary that transcends traditional Eastern and Western art historical categories.

The artist was recently the subject of a solo exhibition at Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai (2018 - 19), and his works are held in numerous public collections, including the Long Museum (Shanghai), M+ Sigg Collection (Hong Kong), and Today Art Museum (Beijing). The artist is represented by David Zwirner.