20th Century and Contemporary Art Evening Sale

New York Auction 2 July 2020

1

Titus Kaphar

Untitled (red thread lady)

Estimate $40,000 - 60,000

Sold for $187,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

2

Matthew Wong

Mood Room

Estimate $60,000 - 80,000

Sold for $848,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

3

Lucas Arruda

Untitled

Estimate $80,000 - 120,000

Sold for $350,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

4

Helen Frankenthaler

Head of the Meadow

Estimate $600,000 - 800,000

Sold for $3,020,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

5

Joan Mitchell

Noël

Estimate $9,500,000 - 12,500,000

Sold for $11,062,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

6

Christina Quarles

Placed

Estimate $70,000 - 100,000

Sold for $400,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

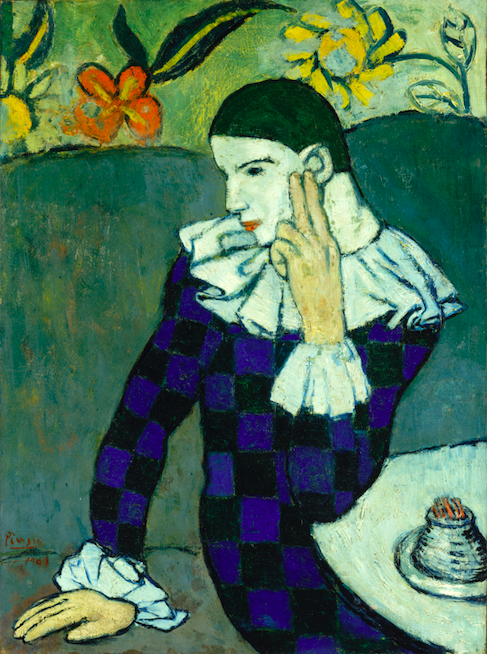

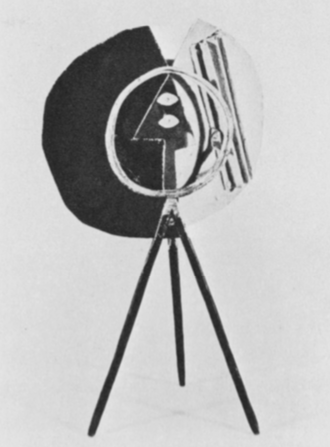

7

Francis Picabia

Portrait de femme

Estimate $250,000 - 350,000

Sold for $350,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

8

KAWS

COMPANION (DETAIL OF CROWD SHOT)

Estimate $1,200,000 - 1,800,000

Sold for $1,380,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

9

Robert Nava

The Tunnel

Estimate $40,000 - 60,000

Sold for $162,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

10

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Victor 25448

Estimate $8,000,000 - 12,000,000

Sold for $9,250,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

11

George Condo

Stump Head

Estimate $900,000 - 1,200,000

Sold for $1,050,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

12

Banksy

Monkey Poison

Estimate $1,800,000 - 2,500,000

Sold for $2,000,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

13

Maxfield Parrish

Humpty Dumpty

Estimate $400,000 - 600,000

Sold for $740,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

14

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe

Shade of Black

Estimate $20,000 - 30,000

Sold for $250,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

15

Charles White

Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child

Estimate $700,000 - 1,000,000

Sold for $800,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

16

Ali Banisadr

Motherboard

Estimate $400,000 - 600,000

Sold for $572,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

17

Gerhard Richter

Abstraktes Bild (801-3)

Estimate $2,000,000 - 3,000,000

Sold for $3,680,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

18

Albert Oehlen

Im Museum II

Estimate $600,000 - 800,000

Sold for $560,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

19

Thomas Struth

Notre Dame, Paris

Estimate $300,000 - 500,000

Sold for $400,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

20

David Hammons

Hidden Drawing (Jordan begins 8th season as No. 1)

Estimate $150,000 - 200,000

Sold for $181,250

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

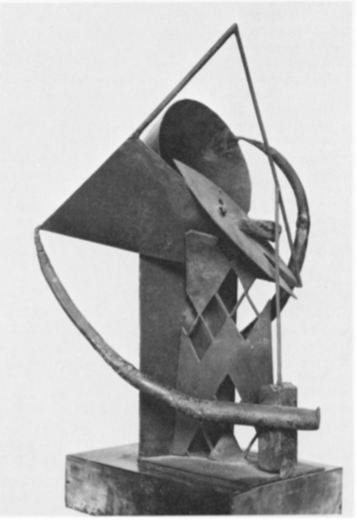

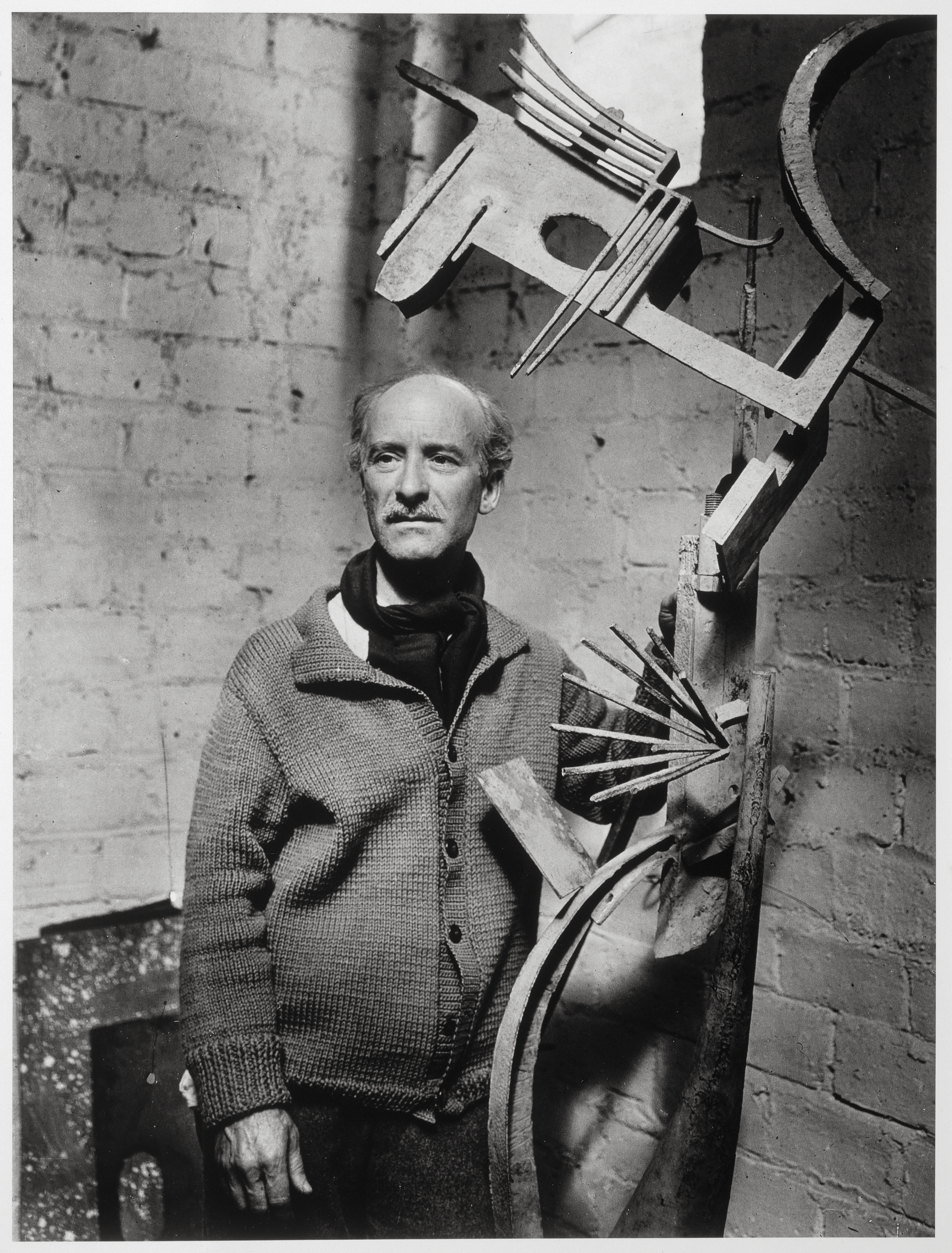

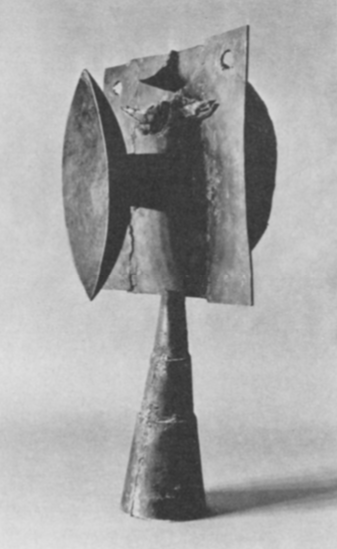

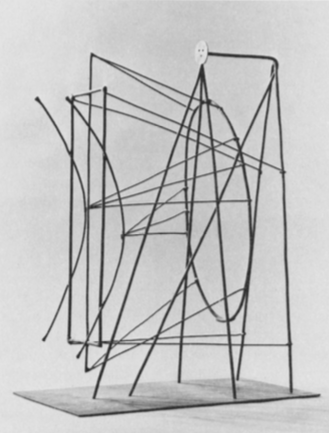

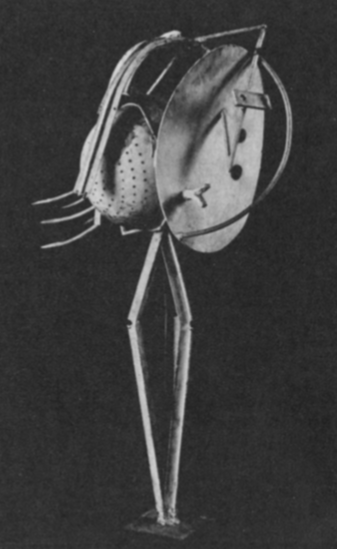

21

Julio González

L'arlequin / Pierrot ou Colombine

Estimate $500,000 - 700,000

Sold for $920,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

22

Amoako Boafo

Joy in Purple

Estimate $50,000 - 70,000

Sold for $668,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

23

Fernando Botero

Woman

Estimate $800,000 - 1,200,000

Sold for $1,004,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

24

Donald Judd

Untitled

Estimate $550,000 - 750,000

Sold for $680,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

25

Sturtevant

Stella Gran Cairo

Estimate $400,000 - 600,000

Sold for $620,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

, 1962-1964_fb2e3246-26bf-433c-a125-74fd78920354.png)

, circa 1888_38c0aa9d-9fea-477a-b278-457617fd3688.jpg)

, 1930_0b716870-42a0-41a4-ba6e-e05d7508b9f8.png)