20th c. & Contemporary Art Evening Sale

New York Auction 7 December 2020

1

Amy Sherald

The Bathers

Estimate $150,000 - 200,000

Sold for $4,265,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

2

Jadé Fadojutimi

Lotus Land

Estimate $40,000 - 60,000

Sold for $378,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

3

Vaughn Spann

Big Black Rainbow (Deep Dive)

Estimate $40,000 - 60,000

Sold for $239,400

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

4

Matthew Wong

Before Night Falls

Estimate $300,000 - 500,000

Sold for $1,252,100

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

5

Ruth Asawa

Untitled (S.045, Hanging Five-Lobed, Multilayered Continuous Form within a Form, with Spheres in the First, Second and Third Lobes)

Estimate $1,500,000 - 2,000,000

Sold for $3,539,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

6

Agnes Martin

Untitled

Estimate $1,800,000 - 2,500,000

Sold for $2,450,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

7

Morris Louis

Infield

Estimate $900,000 - 1,200,000

Sold for $1,179,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

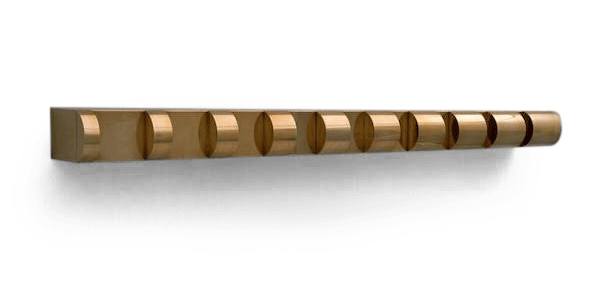

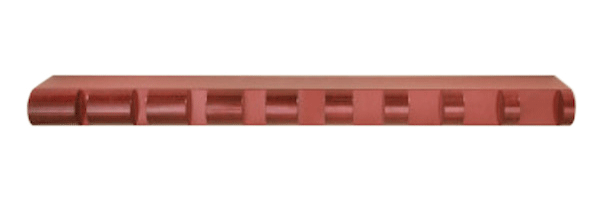

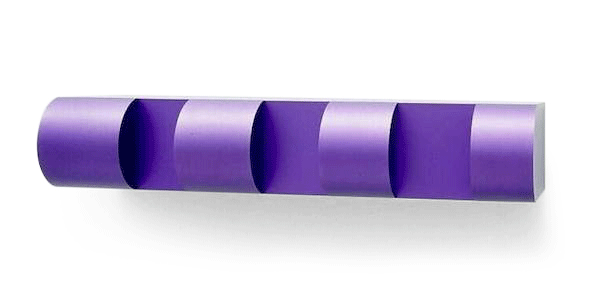

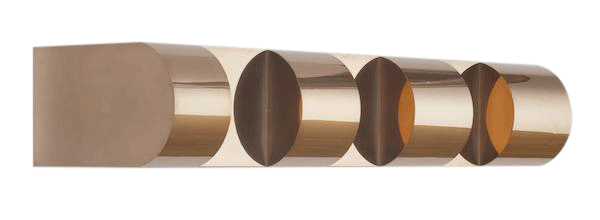

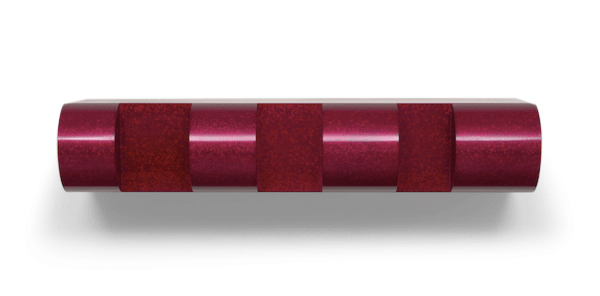

8

Donald Judd

Untitled

Estimate $3,000,000 - 4,000,000

Sold for $3,539,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

9

Richard Diebenkorn

Untitled (Berkeley)

Estimate $300,000 - 500,000

Sold for $478,800

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

10

David Hockney

Nichols Canyon

Estimate On Request

Sold for $41,067,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

11

Amoako Boafo

Purple on Red

Estimate $200,000 - 300,000

Sold for $756,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

12

Barkley L. Hendricks

Selina/Star

Estimate $800,000 - 1,200,000

Sold for $937,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

13

Norman Rockwell

The Peephole

Estimate $1,000,000 - 1,500,000

Sold for $2,087,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

14

Clyfford Still

PH-407

Estimate On Request

Sold for $18,442,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

15

Glenn Ligon

Stranger #67

Estimate $1,400,000 - 1,800,000

Sold for $1,784,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

16

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Portrait of A-One A.K.A. King

Estimate $10,000,000 - 15,000,000

Sold for $11,500,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

17

Titus Kaphar

Veil

Estimate $70,000 - 90,000

Sold for $365,400

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

18

René Magritte

Untitled (Woman's Face covered by a Rose)

Estimate $1,200,000 - 1,800,000

Sold for $2,329,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

19

Norman Rockwell

An Audience of One

Estimate $2,500,000 - 3,500,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

20

Pablo Picasso

Deux personnages

Estimate $1,200,000 - 1,800,000

Sold for $2,147,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

21

Joan Mitchell

Untitled

Estimate $9,000,000 - 12,000,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

22

Gerhard Richter

Abstraktes Bild (678-1)

Estimate $3,000,000 - 5,000,000

Sold for $4,265,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

23

Alexander Calder

Dot + Loop

Estimate $1,200,000 - 1,800,000

Sold for $2,329,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

24

Joan Mitchell

Untitled

Estimate $10,000,000 - 15,000,000

Sold for $11,297,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

25

Roy Lichtenstein

Nude with Joyous Painting (Study)

Estimate $1,500,000 - 2,000,000

Sold for $1,672,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

26

George Condo

Transparent Female Forms

Estimate $3,500,000 - 5,500,000

Sold for $4,265,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

27

Helen Frankenthaler

Off White Square

Estimate $2,800,000 - 3,500,000

Sold for $3,720,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

28

Morris Louis

Beth Sin

Estimate $4,000,000 - 6,000,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

29

Georg Baselitz

Forstarbeiter

Estimate $1,800,000 - 2,500,000

Sold for $2,087,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

30

Charles White

Roots

Estimate $500,000 - 700,000

Sold for $877,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

31

Roy Lichtenstein

Coup de Chapeau I

Estimate $500,000 - 700,000

Sold for $937,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

32

This lot is no longer available.

33

Kehinde Wiley

Portrait of Mickalene Thomas, the Coyote

Estimate $100,000 - 150,000

Sold for $378,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

34

René Magritte

Le Choeur des Sphinges

Estimate $1,000,000 - 1,500,000

Sold for $3,115,500

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

35

Mickalene Thomas

I've Been Good To Me

Estimate $200,000 - 300,000

Sold for $901,200

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

36

This lot is no longer available.

37

Ed Ruscha

Local Storms

Estimate $800,000 - 1,200,000

Create your first list.

Select an existing list or create a new list to share and manage lots you follow.

38

This lot is no longer available.